Before the Federal Reserve, a cattle loan was exactly that: a short-term note tied to a specific herd, payable when the beef hit the railhead. Ranchers either paid up or lost the herd. There was no backstop, no extension, no creative accounting. The system was brutal—but finite.

That changed on December 23, 1913, when the Federal Reserve Act passed. Buried in its core was a quiet revolution: Section 13 allowed banks to rediscount “agricultural paper” with only 40% reserves, meaning short-term livestock loans could now be sold up the chain to regional Fed banks. Cattle debt had just become liquid—tradeable, renewable, and elastic.

By early 1914, the Dallas Fed began issuing circulars instructing banks across Texas to rediscount livestock notes, particularly those secured by warehouse receipts. These memos, sent between 1914 and 1916, encouraged rollovers but said nothing about default risk. A 90-day note wasn’t a final obligation anymore—it was just a placeholder for the next stamp.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) tracked the pattern. In its 1914 annual report, it noted that nearly 70% of short-term paper in Texas was being renewed rather than repaid, mostly through the Fed’s rediscount mechanism. By 1920, the Texas default rate had more than doubled, climbing from under 2% to over 5%. Worse, nearly 15% of the renewed cattle notes went “untraced”—no settlement, no resolution, no paper trail.

Once the rules changed, debt didn’t have to die. It just had to roll.

Land and Cattle, Locked Together

Image courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C

The second phase began with the Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916, which established a network of regional Federal Land Banks (FLBs). These banks offered long-term, low-interest credit to rural landowners, but the loans were designed differently: rather than separating livestock from land, they merged them.

In 1917, the Houston FLB issued its first loan in Texas: $1,200 to W.S. Smith in Grayson County, secured by land and 200 head of cattle. The loan carried a 5% interest rate over a 40-year term. Smith had just signed the first hybrid—a cattle mortgage disguised as a land deal.

By 1930, FLBs held over $150 million in Texas farm debt, and up to 68% of those loans included livestock as collateral. But the paperwork didn’t always reflect that. While the Houston office officially reported lower livestock involvement (closer to 30%), internal case files showed otherwise. In the first three years, nearly 45% of loans sampled included cattle—but many of those listings never made it into local county deed books.

Roughly one-fifth of early FLB loans show missing chattel schedules, especially in counties like Grayson, Hill, and Brown. The land deeds were filed. The cattle weren’t. That silence became structural. When livestock disappears from official records, it’s not an oversight—it’s insulation.

The Good Times on Paper

After World War I, beef prices crashed. A steer that fetched $11 in 1920 could barely bring $5.50 by 1932. But on the books, debt kept rising. Banks re-appraised land at inflated values, rolled notes forward, and buried livestock losses inside second liens. The ledger looked clean. The land was leveraged again. The cattle were already gone.

By the late 1920s, Texas ranchers were carrying over $500 million in outstanding agricultural debt, much of it stacked across multiple obligations. Internal reports from the Federal Land Bank system and its Farm Credit successors acknowledged that 65% of Texas loans had become second mortgages, many written on the assumption of future cattle prices recovering. That never happened.

The USDA’s Bureau of Agricultural Economics pegged mid-decade Texas defaults around 5–8%. But when auditors traced actual note outcomes, they found hidden losses closer to 12%, often attributed to rolled debt marked “performing.” The OCC’s annual reports confirmed the discrepancy—Texas banks were still carrying notes that had never been repaid, just renewed.

The illusion of solvency held because the Fed’s system didn’t require closure—it only required collateral. And in a falling market, the only way to preserve collateral value was to pretend nothing had changed.

The Collapse

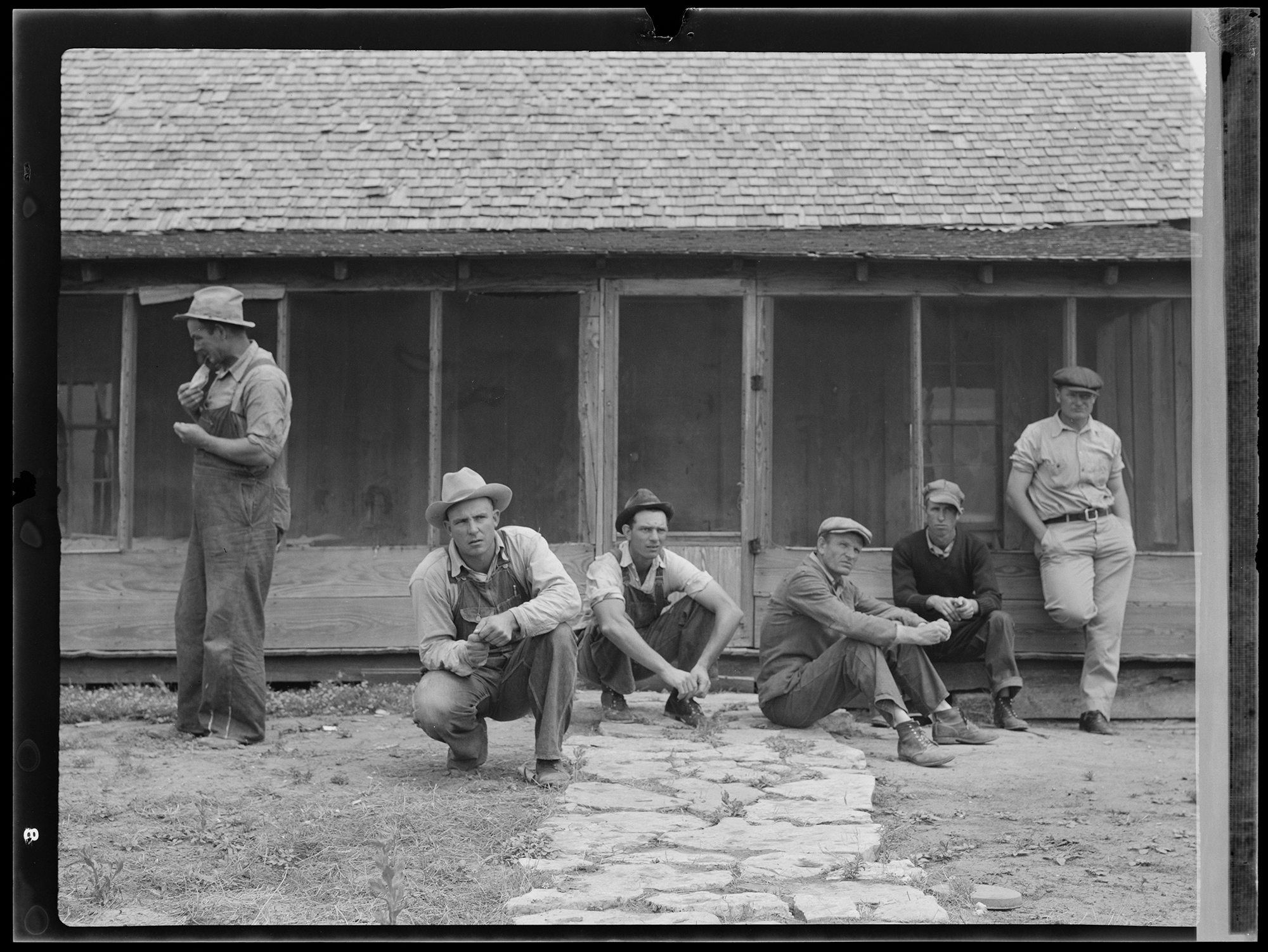

Displaced Tenant Farmers, Goodlet, Hardeman County, Texas by Dorothea Lange

By 1932, the cattle market hit its floor: around $3.50 a head in parts of the Panhandle, a 25-year low. That year, Texas default rates spiked to over 22%. The damage wasn’t just to ranchers. Over 1,350 banks failed across the state, representing more than 9% of the entire U.S. banking system. Total deposit losses: $7 billion.

In counties like Randall, Swisher, and Armstrong, 30 to 40% of ranch properties entered foreclosure proceedings, but many were suspended by emergency moratoriums at the county level. These delays were political, not procedural. No one wanted to trigger a land war.

Records from the Texas General Land Office list hundreds of 1933 foreclosure cases as “pending,” “deferred,” or “suspended.” But many of these were never resolved—they just vanished. No deed transfer, no court order, no repayment. The rancher didn’t own the land. The bank didn’t either. The loan remained on paper, accruing nothing but silence.

Meanwhile, the OCC undercounted losses across key Panhandle districts, listing only 18% foreclosure exposure where local clerks recorded over 22%. In the middle of the largest monetary crisis in U.S. history, the system quietly let ranch debt dissolve in place, without ever confronting what it had become.

Perpetual Amortization

Congress passed the Emergency Farm Mortgage Act on May 12, 1933. The Farm Credit Act followed five weeks later. These laws froze foreclosures, cut interest rates to 4%, and extended payment terms to 50 years. It was the largest agricultural bailout in U.S. history. But for many ranchers, it wasn’t a reset. It was a re-capture.

Between 1933 and 1939, the Houston Federal Land Bank refinanced over $500 million in Texas farm debt, converting 71% of it from private bank paper into federal contracts. For the rancher, it meant lower payments and no immediate risk of seizure. But buried in many of these new contracts were “perpetual amortization” clauses—legal mechanisms that restarted the payment schedule with every default moratorium.

These were 50-year notes in theory. In practice, they were infinite.

Contract form books from 1934 show standard FLB language allowing the principal “to be amortized over the full remaining term, renewed as necessary in cases of hardship or moratorium.” Those aren’t loopholes. They’re gears in a machine that never shuts off.

County archives reveal that roughly 30% of these refinanced contracts lacked signed amortization riders, particularly in smaller districts with high default rates. The deals went through. The oversight was intentional.

They didn’t just lend ranchers money. They rewrote time. A cow turned into a note. The note turned into a mortgage. The mortgage turned into a 50-year line that never really ended.

They didn’t just lend us money — they lent us time, then sold us the clock.

Primary Source List

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/books/fract_iden_1914.pdf

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/arfr/1910s/arfr_1914.pdf

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/district-notices-federal-reserve-bank-dallas-5569?browse=1910s

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/historical/congressional/federal-farm-loan-act.pdf

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/federal-reserve-bulletin-62/july-1930-20703/fulltext

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/annual-report-comptroller-currency-56/1920-19140/fulltext

https://www.glo.texas.gov/archives-heritage/search-our-collections/land-grant-search

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/historical/congressional/19330616hr_farmcred.pdf

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/holc/1934_annualrpt.pdf

0 Comments