On July 7, 2025, the USDA will reopen the U.S.-Mexico cattle border under a phased biosecurity protocol. The agency insists the move is justified: no northward screwworm spread in eight weeks, a surge in sterile fly deployment, and updated import restrictions that appear to contain the risk.

But behind the bureaucratic calm is a storm of dissent—centered not just on pest control but on power, profit, and who gets to define “small producers” in a globalized beef economy.

As the reopening approaches, long-running tensions between independent cattle producers and multinational-aligned trade groups are surfacing again. A recent exchange on social media—sparked by NCBA’s former International Trade Committee Chair Jaclyn Wilson—highlighted what many in the industry already knew: the fight isn’t just over border protocols. It’s over who the U.S. cattle industry serves—and who it sacrifices.

Reopening the Border: A Political Move Dressed as Science

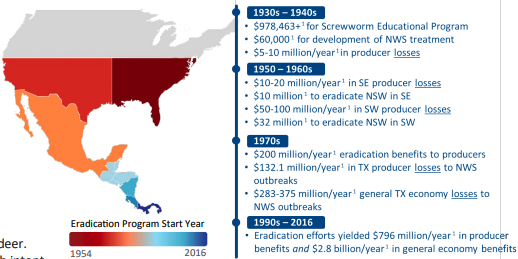

The New World Screwworm (NWS) is a flesh-eating parasite eradicated from the U.S. in 1966 through a landmark sterile fly program pioneered by the USDA. The program pushed south through Central America over the following decades, with a permanent biological barrier eventually established at the Darien Gap in Panama.

But the parasite has surged back. In 2023, Panama reported over 6,500 screwworm cases, up from an annual average of 25. By early 2025, infestations had spread through Central America and into Mexico, reaching as far north as Oaxaca and Veracruz.

In response, the USDA suspended imports of cattle, bison, and equines in May 2025. The move aligned with warnings from R-CALF USA and others who cited the historical risk of reintroduction—an event that, in 1976 alone, cost Texas producers the equivalent of $732 million in today’s dollars.

Yet even before the border closure, pressure from trade-aligned voices began mounting. Critics of the USDA’s suspension called it unnecessary, citing industry need and the economic reliance of U.S. feedlots on Mexican yearlings. The NCBA—which has long opposed mandatory country-of-origin labeling and supported equivalency deals that blur the line between foreign and domestic cattle—was among those urging a swift return to “normal.”

Who’s Really Hurt by Import Suspensions?

Wilson’s July 5 post criticized R-CALF for advocating a continued closure, claiming such a stance “hurts small producers.” That claim raised a critical question: what kind of producers rely on cattle from Mexico?

Not the family rancher running a closed herd in Montana, Nebraska, or Texas. Not the cow-calf operator calving on native pasture and finishing local. Those ranchers need fair markets, reliable local processing, and biosecurity protections—not foreign feeders.

The true stakeholders in the push to reopen the border are:

- Large-scale feedlots, especially in border states like Texas and Arizona, whose profitability depends on year-round feeder cattle supply;

- Multinational packers like JBS and Cargill, who benefit from volume imports and price suppression;

- Integrated backgrounders and custom grazers contracted by downstream players.

As of mid-2025, even with suspensions, Mexico had already shipped 1.2 million head to the U.S. this year—a 13.2% increase over 2023. The November 2024 suspension alone was estimated to cost the industry 250,000–300,000 head.

Those are not “small producers.” They are industrial-scale players with lobbying arms, trade attorneys, and congressional connections.

Risk Shifted to the Rancher

The USDA’s phased reopening includes narrow geographic allowances: cattle and bison from Sonora or Chihuahua—or those treated under New World Screwworm protocols—may enter. Equines must meet additional quarantine requirements. A new facility in Metapa, Mexico, is under construction to boost sterile fly production to 100 million per week by mid-2026, with long-term goals of restoring the Darien Gap barrier.

But the underlying risk hasn’t disappeared.

Screwworms don’t respect livestock-only barriers. They can travel in wildlife, pets, even human hosts. Surveillance may detect symptoms—but not until after the spread has begun. And unlike the NCBA or trade-aligned yards, it’s the independent producer who bears the cost of infestation, treatment, and loss.

“This could spread to our American herds by reopening the ports in Mexico,” Meriweather Farms reported on X, “Why would the USDA want to put American cattle and American ranchers at risk?“

R-CALF’s Position: Protect the Herd First

R-CALF USA, which has long battled NCBA over issues like antitrust enforcement and country-of-origin labeling, has taken a firm stance: no imports until screwworm is contained.

They’ve:

- Supported USDA’s initial import halt

- Requested FDA authorization for ivermectin feed-through treatment

- Urged investigations into market manipulation and premature reopening narratives

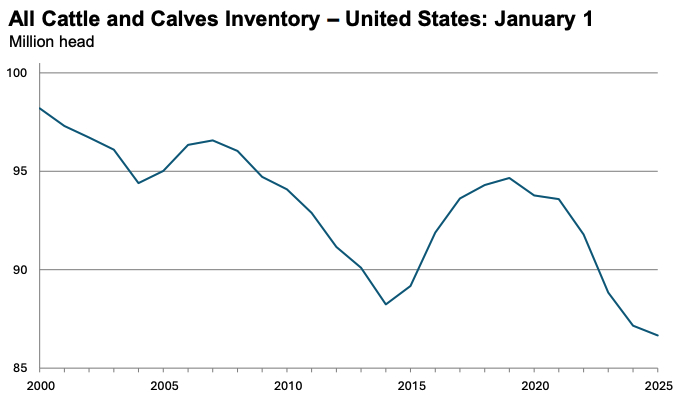

Their concern isn’t hypothetical. The national herd has already contracted by roughly 2% in 2025. Reintroducing screwworm under these conditions would be devastating.

R-CALF CEO Bill Bullard has framed the issue not as isolationism, but as basic national security. In his view, the current USDA reopening plan favors short-term trade volume over long-term herd protection—and serves the same industrial interests that have consolidated meatpacking, crushed rural processing, and hollowed out price discovery.

Manufactured Consent in the Name of the “Small Producer”

The most revealing aspect of this conflict is the language.

When trade groups and their allies invoke “small producers,” they rarely mean the ranch family calving in February and branding in June. They mean vertically aligned suppliers, contract backgrounders, or feedlot operators serving downstream volume contracts.

The conflation isn’t accidental—it’s a strategy. If packers and feedlots can wrap their global sourcing ambitions in the image of the independent rancher, they can push deregulation and border reopenings without resistance. But the true cost of that deception—disease risk, market pressure, and genetic dilution—will land squarely on the backs of those never consulted.

Conclusion: Biosecurity for Whom?

The July 7 reopening is more than a policy shift. It’s a litmus test.

Does USDA exist to protect U.S. producers—or to keep foreign cattle flowing for the benefit of consolidated processors and industrial feedyards?

Is “science-based policy” just a euphemism for trade convenience?

And most of all: when the next biosecurity failure occurs, will anyone admit that the warning signs were buried under profit motives and polite press releases?

R-CALF says close the border until the threat is gone. NCBA says trust the system and keep the cattle moving.

Only one of them is standing up for the people who raise the beef. You decide who that is.

Want to find beef raised by the ranchers actually fighting for this country? Visit BeefMaps.com and shake your rancher’s hand.

0 Comments