UPDATE: Rep. Harriet Hageman defended the Senate proposal in a June 21 column, emphasizing that any land sales would require consultation with governors, tribal governments, and local officials. She framed the bill as a targeted solution for housing shortages, not a mass land grab. But with other sections of the bill—like those governing “AI Systems”—explicitly overriding local zoning authority, it remains unclear how much influence those local entities will actually retain once land is nominated.

The fence post is still there, hammered into the high desert decades ago. On the other side: land meant to fund local schools, stewarded by state agencies, and managed under trust law.

Today, it sits untouched—not because no one needs it. But because someone sued.

This is the quiet power of the Endangered Species Act (ESA)—and specifically its private right of action, a legal mechanism that allows activist nonprofits to stop land use dead in its tracks. And in 2025, as the Senate debates a plan to sell off 3.3 million acres of federal land, this obscure provision has become the silent engine driving a radical shift in who controls America’s terrain.

But lawsuits are only half the story. The other half is what happens after the land is sold.

A Two-Lane Lockdown

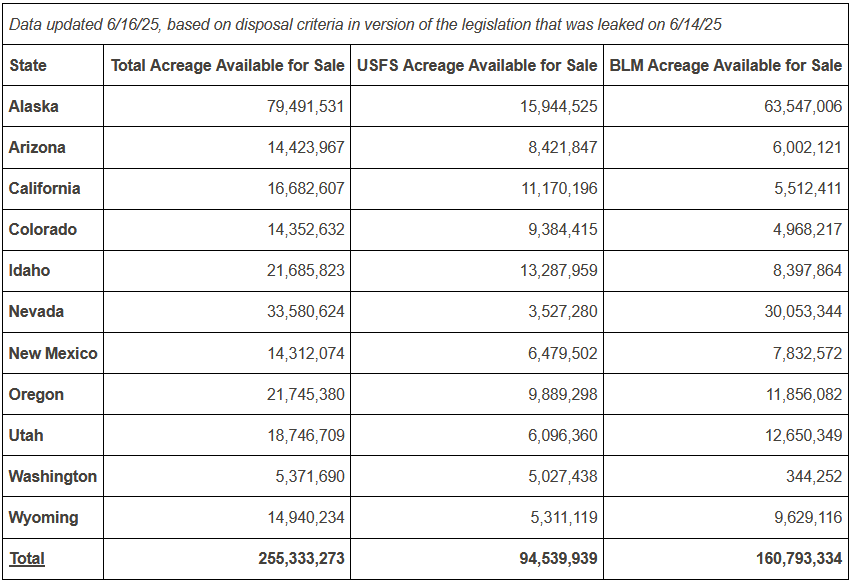

On one side, the Senate Reconciliation Bill (H.R.1) proposes to sell 2.2 to 3.3 million acres of BLM and Forest Service land—roughly 0.5% to 0.75% of Western federal holdings. But buried in the fine print is something more dangerous: the bill makes over 250 million acres eligible for private nomination, with no public input, no affordability mandates, and no obligation to reveal who buys the land.

Even more alarming is Section 43201(C) of the bill, which critics have argued could prohibit state or local governments from regulating land use due to its overly broad language of “AI systems.”

Critics, including Beef Initiative policy analyst Breeauna Sagdal, note this section’s vague and expansive language could unintentionally nullify local regulations beyond AI, potentially affecting land use if AI tools are involved.

Examples include; local laws addressing algorithmic bias in housing development, or criminal justice such as the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) system, or predictive policing systems—banned by many municipalities across the country.

Others have argued that “A.I. Systems” could be interpreted by applicable administrative agencies (who serve at the pleasure of the President) to mean data centers or physical locations. At which point, local zoning would be impacted due to the preemption right granted to the federal government for ten years.

Said plainly: the bill doesn’t just sell the land. It preempts local control, creating a sizable gamble dependent upon who occupies the White House.

The Lawsuit Economy

On the other side of the legal equation are state lands held in trust—parcels granted to states to generate revenue for public schools, and offset taxes. Many of these parcels sit undeveloped, not because of market conditions, but because of Endangered Species Act (ESA) litigation.

Under Section 11(g) of the ESA, groups like the Centers for Biological Diversity (CBD) have been incentivized to sue state and federal agencies, making millions in the process, while strong-arming policy changes.

A single lawsuit can halt any project—grazing, wildfire mitigation, even school infrastructure.

CBD claims a 93% success rate in court and funds operations in part through attorney fees recovered in those wins. Their litigation model has shaped national land use policy—and generated millions in the process.

Meanwhile, state lands held in trust go unmanaged. Fires spread. Revenues vanish. And the public never gets to vote on any of it.

This Isn’t Just a Land Sale. It’s a Lockout.

While the Senate bill is framed as a housing solution, the vast majority of BLM and Forest Service lands are located far from existing infrastructure. According to Headwaters Economics, only a small fraction—estimated at under 2%—is near communities where housing is in demand. Moreover, the bill includes no language requiring affordability, density, or public-serving outcomes, leaving open the potential for luxury or speculative development.

Combine that with Section 43201’s 10-year ban on state regulation of AI, potentially impacting local land use regulations, and various federal regulations related to land acquisition and eminent domain use, and a different picture emerges.

This isn’t about homes.

It’s about hubs.

Data hubs.

Energy hubs.

Logistics corridors.

The skeleton of future smart cities, quietly grafted onto formerly public land.

Legal Reform? Don’t Hold Your Breath.

In early 2025, the Trump administration proposed narrowing the ESA’s definition of “harm” to exclude habitat destruction—an attempt to reduce litigation chokepoints. But the core legal weapon—the private right of action—remains untouched. Only Congress can repeal it.

Until then, public lands remain open to two paths:

Locked up by lawsuits.

Or auctioned off beyond local control:

Either way, private property rights are at risk, despite online claims this is a solution to the 30×30 goals of Agenda 2030.

Conclusion: A Pattern, Not a Policy

When land is frozen by lawsuits or stripped from local control after sale, what’s left is neither protection nor progress. It’s a transfer—of power, of access, of rights.

The ESA’s citizen suit provision, once a tool for public accountability, now acts as a blockade on state and rural land use. The Senate’s land sale bill, branded as a housing fix, hides within it the legal infrastructure of exclusion: top-down sales, bottom-up litigation, and the complete removal of local say.

It’s not just about the land.

It’s about who gets to pull the lever of control.

A risky unknown, pending future election results.

Want to know who still answers to the people? Find your local, independent rancher at BeefMaps.com—where land use still means feeding families, not feeding the grid.

0 Comments