The Texas Panhandle didn’t fall to war—it was sold off, one section at a time, in exchange for a building and a promise.

By 1882, the Texas Legislature had grown tired of delays. The Capitol in Austin needed to be rebuilt. There wasn’t enough gold in the treasury to pay for it. So the state reached for what it still had in abundance: land.

It was one of the largest land-for-infrastructure swaps in American history.

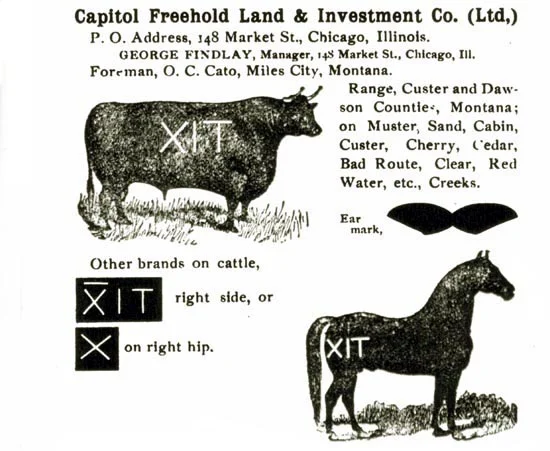

But the deal didn’t begin in Austin. It began in Chicago—with Mathias Schnell and the bond he filed to secure the first $250,000. Within months, his stake flipped to Taylor, Babcock & Company. By spring, it was John V. Farwell’s turn. Backed by British capital and fueled by London debentures paying five percent, he incorporated the Capitol Freehold Land and Investment Company, Ltd. in London in late 1884 and began fencing Texas before most Texans even knew what the word syndicate meant.

This wasn’t a cattle outfit—it was a British bond fund with a herd problem.

Cattle were never the goal. They were a hedge. The bond was the asset. The land was the guarantee.

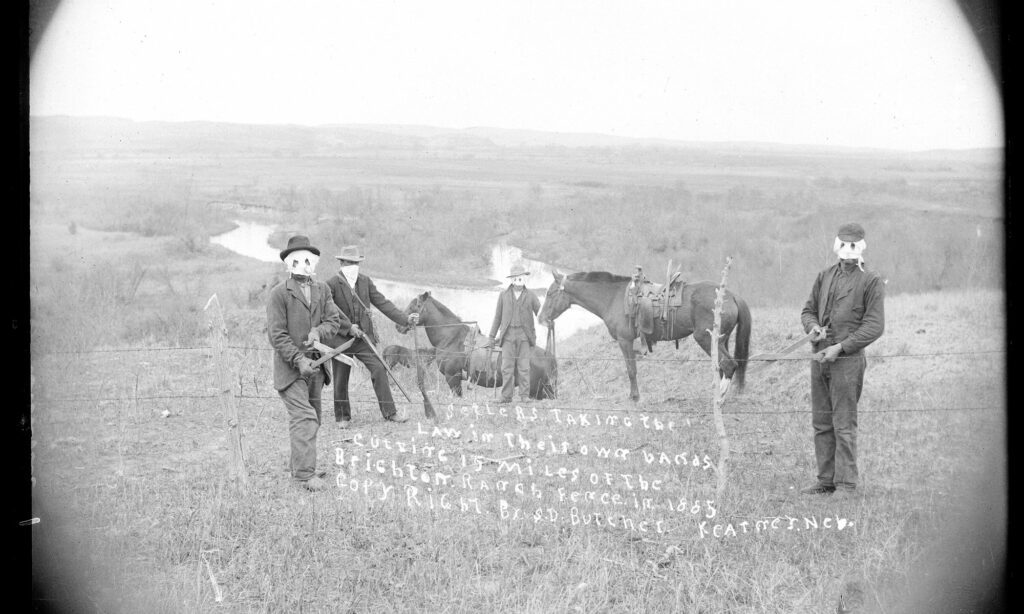

The Bond-Fence

The fence was more than barbed wire—it was infrastructure for speculation.

Payroll logs from the Panhandle-Plains archives show over 150 riders on the books, guarding not just livestock but liens. Inside the fence, there were rules. Outside, there was still Texas.

They fenced it to secure the bonds.

The stock was tallied. The calves were branded. Prairie fires were logged, windmills inventoried, and every corner of the land grid was mapped—not for grazing, but for liquidation. The goal was to subdivide. The cattle just paid the bills in the meantime.

And while Texas cowboys built the ranch, British bondholders owned it.

The debentures weren’t speculative—they were tied to acreage, livestock, and range infrastructure. By 1887, 150,000 head had been driven through the gates. Each was logged, mortgaged, or sold. The ranch was collateral. The land was yield.

When over 200 miles of fence were cut during the 1883–85 Fence Wars, only a handful of indictments followed. Of the fifteen prosecuted, zero were convicted. XIT manager A.T. Campbell was removed in 1887 after a state investigation revealed evidence of mismanagement and rustler protection. No further action was taken.

The books stayed open. The records stayed incomplete.

Was it incompetence? Maybe. But there’s a pattern in the gaps.

Liquidation by Drought, Silence by Design

Drought is an honest killer. It doesn’t need a conspiracy to drain the plains.

The crashes came early. A hard freeze in 1886 followed by a bone-dry 1887 scorched the heart out of the herd. USDA reports from the era estimate over $20 million in losses across the Southern Plains. XIT stock slowed. By 1891, the rains failed again. Grass went brittle. The Syndicate began to sell.

Records show that by 1905, nearly 800,000 acres had been subdivided and sold off.

The herd never recovered its peak. The rail shifted south, pulling the market with it. Amarillo auctions outpaced XIT shipping lanes. By 1910, the bond redemptions were wrapping up.

But that’s when things get quiet.

Texas Treasury audits between 1890 and 1909 show at least fifteen percent of bond redemptions listed as “untraced.” No single entry pins that gap to the XIT, but Farwell correspondence from Chicago references off-record land transfers. Meanwhile, county court filings in the ten Panhandle counties where the XIT operated show irregular deed trails—missing liens, delayed filings, and in some cases, parcel IDs without origin surveys.

No fires were officially logged in Hartley or Dallam counties during that liquidation period. But multiple courthouse fires across other ranch-heavy counties between 1880 and 1910 erased swaths of brand records, deed receipts, and chattel lien documentation.

What’s left behind isn’t proof. But it’s a trail of silence that matches a pattern.

A ranch that began as a public land deal ended in a private wind-down—no taxes on exported profits, no final audits, no ledger of who truly walked away with the most.

The Pattern Still Holding

This wasn’t a ranch. It was a rehearsal.

Imported credit. Texas labor. Exported yield.

Cowboys earned their keep—$25 a month, plus bounties for wolves and strays—but they had no stake in the land they branded. Their names don’t appear in the British ledgers. Their stories ended in payroll stubs.

By the time the cattle left, the land was already sliced for resale.

By the time the bondholders redeemed, the books were already closing.

And by the time Texans realized the scope of what had passed through their fence lines, the Syndicate had vanished back into London vaults.

No one was arrested.

No one was fined.

The fence held. The truth didn’t.

A New Ledger Rides In

In 2021, a small nation in Central America passed a law.

It wasn’t about cattle. It was about sovereignty.

El Salvador made Bitcoin legal tender.

Then came the blueprint: volcano-backed sovereign bonds, pegged to energy instead of fiat. Approved in early 2024, these bonds haven’t been floated yet—but the design is familiar: hard assets, local production, peer-verifiable trust.

It’s the same framework Goodnight once used to build the JA.

It’s the same wire Adair ran through Wells Fargo to fund the range.

And it’s what the Capitol Syndicate twisted into a fence.

Today, we call it blockchain.

Then, it was a ledger on hoof.

Both begin the same way: one honest asset, peer to peer, no middleman.

The land still remembers.

So do the cowboys.

They fenced the land to keep the cattle in.

They filed the records to let the money out.

This time, we keep the keys.

0 Comments