Retrospective Policy Paper by Door to Freedom

A lot of ink has been spilled over the USDA’s recent cancellation of a $1.1 Billion program intended to provide fresh, locally raised food to schools, food pantries, and disadvantaged individuals. The program certainly looked like a triple-win program for small farmers, children and the poor. Their champions have accused the USDA of taking food from the mouths of babes. However, USDA is releasing funding for existing agreements and is not reneging on any programs. It simply announced that it will not be carrying out another funding round for this program, which had been crafted to manage supply chain interruptions during the pandemic.

In response, the national School Nutrition Association arranged for over 800 of its members to visit Congress on March 11, demanding the funding be restored. A group of Democrat Senators promised to support them with a letter to the USDA Secretary. And on March 12 Senator Fetterman filed a bill to cancel all student lunch debt across the country, which amounts to about $176 million a year.

But what none of the media have done is examine how this USDA program came to be, how it is funded, how the United States provides food aid to its citizens and how federal programs designed to help Americans obtain a healthy diet might need a serious overhaul.

What does food aid cost the United States?

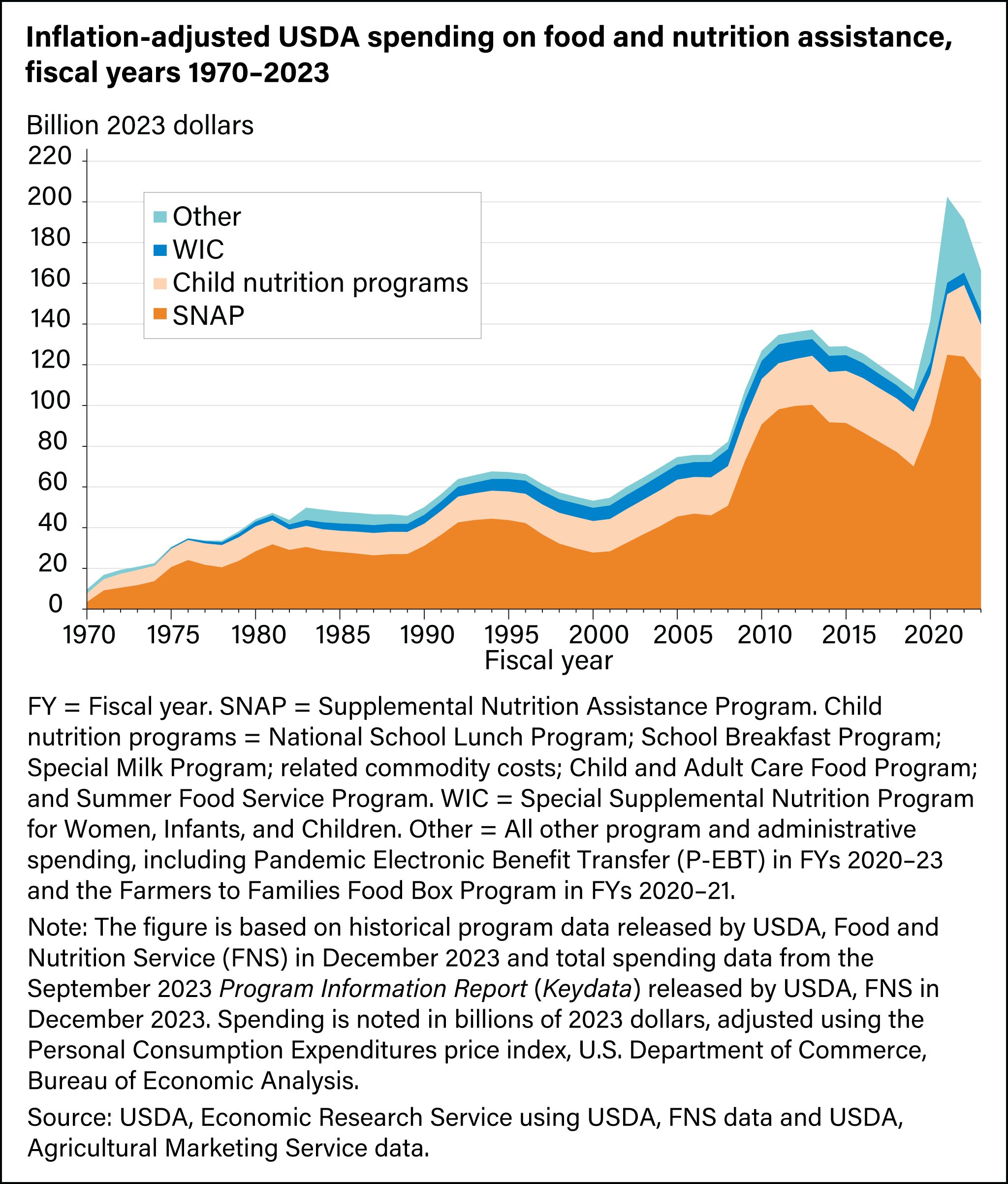

Very few people know that USDA spent over $200 Billion dollars in 2021 (during the pandemic) on food and nutrition assistance for Americans. After the pandemic ended, it spent $166.4 Billion in 2023 on a variety of programs. The 2023 level of spending is equivalent to $500 collected from every single American for just one year. Taxes must cover this cost.

A full list of USDA beneficiary programs for food and nutrition in 2023 is included in the Appendix.

The US Government believes that 10-15% of schoolchildren are food insecure, but this assessment may not be accurate.

18 million American households were designated as food insecure for some period of time during 2023, or 13.5%. This number is extrapolated from self-reporting to US census-takers, who collected detailed information on diet from about 30,000 US households.

However, according to USDA’s Economic Research Service,

“About 58 percent of food-insecure households participated in one or more of the three largest Federal nutrition assistance programs from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); and the National School Lunch Program during the month before the 2023 survey.”

If these numbers are correct, why did 42% of the food-insecure households receive no food benefits from the USDA’s 3 largest programs? Are millions of households that are not thought to be food-insecure receiving the benefits? How close is the match between needy families and actual beneficiaries?

In 2023, 42 million Americans or 12.5% of the population received SNAP benefits. SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program was previously called the Food Stamp program. It was created about 60 years ago. Low-income Americans who meet income and other guidelines can receive up to $292/month for a single person, and up to $973/month for a family of four in the continental United States. The benefits are higher in Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and other non-contiguous territories. Beneficiaries receive an EBT card, which works like a debit card, but may only be used to buy food and non-alcoholic beverages.

Approximately 10% of overall SNAP funds are spent for soda and other sweetened drinks. There has long been discussion of whether soda should be excluded from SNAP benefits, but the sugar and soda industries have effectively lobbied to retain unhealthy drinks, even going so far as to fund organizations that accuse those who wish to reduce soda consumption as racist.

How much is spent on the school lunch program?

The federal school lunch program actually includes breakfasts and after school-snacks in addition to lunches for beneficiaries, and cost over $22 Billion dollars in 2023, or the equivalent of $67/year contributed by each American. If we canceled school lunch debt and provided free lunches for every school child, it would cost roughly 2-3 times this much.

Eight state legislatures have already chosen to provide free meals to all of their school students. In Maine, the state’s budget for these meals is estimated at $70 million dollars for 172,000 schoolchildren, with additional contributions by the federal government.

What is the reimbursement rate for school meals?

The federal government provides approximately $7.60 per child per day to cover breakfast ($2.37), lunch ($4.01) and an afterschool snack ($1.21) (for those in the afterschool program). Schools may also offer reduced-price meals, with most of the cost paid by the federal government, and schools usually also sell food items to students. School cafeterias are obviously on a tight budget, with few being able to provide nutritious meals, generous portions, and local food on the federal allotment, while still complying with the USDA’s nutrition guidelines. So what do they do?

Most schools outsource some or all of their meal prep to “Big Food” catering companies. Their selections are notably high in sugar, salt and fried foods. Despite efforts by large catering companies to make the foods tasty for children, students generally prefer the “meals from scratch” to the industrial “heat and eat” selections in school cafeterias.

While the School Nutrition Association refers to a study claiming that school lunches are the most nutritious meal of the day for schoolchildren, what we know is that most of the meals are sorely lacking in nutrition, and contain excessive amounts of sugar, other carbohydrates and ultra-processed ingredients that are relatively depleted of nutrients.

In recent years, Big Food companies — and their industry associations — have spent millions of dollars lobbying the federal government to weaken or change its nutritional standards, and these efforts have paid off handsomely. It happened in 2014, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) caved to industry pressure and made it easier for schools to serve French fries and pizza. It happened in 2018, when the USDA loosened restrictions on the amount of sodium, flavored milk, and refined grains that could be served in school meals….

When the National School Lunch Act was passed in 1946, school food program directors — many of them trained in home economics or dietetics—persuaded Congress that for-profit operators had no place in the not-for-profit world of the federal lunch program…. Facing intense pressure also from the National Restaurant Association, a powerful trade lobby representing the food service industry (and often referred to by food justice advocates as “the other NRA”), the USDA then decided, in 1970, to lift its restriction on for-profit providers...

How have America’s children done? We are seeing the highest rates ever of obesity and diabetes in children. CDC’s chart of childhood obesity below, spanning 55 years, ends 7 years ago, but things have only gotten worse since then.

Here is another useful federal chart of childhood obesity, with a breakdown by race/ethnicity, which comes from America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2023

The rate of type 2 diabetes in adolescents doubled between 2000 and 2017, and the rate of type 1 diabetes rose as well.

The federal government went to great lengths during the pandemic to provide food aid to children and poor adults. These programs were not expected to extend beyond the pandemic.

For example, during the pandemic,

“The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) waived the eligibility requirements for free lunch to allow school meal programs to provide safe, free healthy meals to all children and these flexibilities were extended through June of this year.”

In addition, to compensate for school closures, expanded pandemic benefits for children (termed P-EBT) were made through the SNAP program, and income restrictions for free school meals were waived. When schools were shut, the federal government paid schools to produce and package up meals that were sent to families at home, using school buses as food delivery vehicles.

Two additional food benefit programs were created during the pandemic. One was the 2022 Local Food for Schools (LFS) Cooperative Agreement Program. Each program was designed to support socially (and not necessarily economically) disadvantaged producers, who were defined by LFS in its FAQs:

“Q6. The RFA says that purchases must target socially disadvantaged farmers and producers and small businesses. Can you expand more on what is meant by socially disadvantaged producers? Are purchases limited to those producers or is this just a target?

A6. For the purpose of this program, “socially disadvantaged” is a farmer or rancher who is a member of a Socially Disadvantaged Group. A Socially Disadvantaged Group is a group whose members have been subject to discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and, where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program.”

Funding for the LFS program came from the USDA’s Commodity Credit Corporation.

The other new program, the Local Food Purchase Assistance (LFPA) Cooperative Agreement Program was also initiated in 2022. It was designed to serve socially disadvantaged producers and recipients. Funding for the initial year of the program came from Congressionally authorized funds. But funding later came from the Commodity Credit Corporation, when the program was renamed LFPA-Plus.

The non-competitive, cooperative agreements, “allow the states, tribes and territories to procure and distribute local and regional foods and beverages that are healthy, nutritious, unique to their geographic areas and that meet the needs of the population… and to maintain and improve food and agricultural supply chain resiliency” Furthermore, there was a goal to “expand economic opportunity for local and underserved producers.”

While these were all salutary goals, the initial grants invited abuse, as the producers and recipients included as beneficiaries were selected in a non-competitive manner. NGOs or for-profit companies were chosen to receive grants by the states, who carried out the work program. For example, Vermont’s SUSU CommUNITY Farm received an initial $45,000 to provide, “a no-cost box of african diasporic and culturally relevant foods, herbal medicinals, eggs, flowers and other items each week for 20 weeks to 45+ families in Windham County, Vermont.” This organization’s 2022 IRS Form 990 indicates it delivered 1,330 boxes of food (under other contracts) at an overall cost of $234 per box.

Shortly before leaving office, the Biden administration issued another funding opportunity for these 2 programs, offering the states approximately $660 million in grants for LFS and $440 million for LPFA-Plus. But by then the pandemic was over.

The grants were designed to provide local fresh produce, meat, eggs and dairy to local consumers. This is exactly what local food producers and consumers desperately need. But while one more set of grants to a plethora of community organizations would have been helpful, the grants were associated with limited state or federal oversight and no plan for continuity. They would not have provided a solution to the problem of America’s overall reliance on industrial food, which begins in the school cafeterias.

A dive into the source of program funding revealed a slush fund within USDA

The Biden administration’s 2024 offer of another year of LFS and LPFA programs tapped a little-known source of funds that is essentially outside Congressional oversight.

Nearly 100 years ago, during the Great Depression, a fund (the Commodity Credit Corporation) was created within USDA that could be drawn on to control commodity prices and keep farmers from bankruptcy in bad years. Over time, this fund grew to $30 Billion dollars year, which could be drawn from the Treasury at the will of the Secretary for a variety of purposes. These purposes included climate-oriented programs, and programs favoring politically important regions. Both parties have been accused of using this considerable source of funding, not specifically authorized by Congress, for political purposes. This is how the LFS and the LFPA -Plus were funded under the Biden administration.

Should ad-hoc funding for an idiosyncratic food program be coming from a slush fund? Shouldn’t Congress limit the purposes for which this fund can be used to its original intent, and shouldn’t the government be restricted to only spending funds clearly authorized by Congress?

The federal debt and the contribution of our food programs to it

During the last fiscal year, the federal government spent $1.8 trillion dollars more than it took in. $1.8 trillion dollars of debt, divided by the number of Americans, means each of us is responsible for $5,300 in debt, for last year alone!. Some of that debt is due to interest payments on the cumulative federal debt, which now costs $1 Trillion dollars a year to service, or about $300 dollars per person. The total federal debt of $36 Trillion dollars is equivalent to more than $100,000 for each American. That is how much our government has borrowed, pp, and we are placing that debt on our children’s and grandchildren’s shoulders.

This is why it is critical for the US to get its spending under control. Congress has proven they will kick this can down the road forever. They want as much money as possible spent in their district to influence votes for the next election. It is only the President, especially because he will not be running for office again, who can begin managing our massive debt.

SOLUTIONS

1. The 2 canceled programs were idiosyncratically designed, ad hoc, without guardrails, for the pandemic. Rather than reissuing them, an expanded program for purchase of local food from local providers should be created, with clearer guidelines for the economically disadvantaged–both producers and recipients. Beneficiaries should be able to choose the foods they want, rather than being provided with a selection of foods chosen by a local vendor. Year-to-year continuity should be established.

An improved program could be an expansion of the Farm Fresh Rewards program in Maine, which allows shoppers to use their EBT benefits to pay half price for fresh produce at participating sellers, including groceries, farm stands, food co-ops and health food stores.

2. School meals, despite meeting federal nutrition guidelines, are not healthy. Most free school meals are currently being provided to students who are not food-insecure. The schools have taken over the role of the parents.

There should be a required needs assessment for free meals, while the federal allotment per meal should increase considerably. American school lunch programs were initiated to support children in need, not all children. While universal meal provision is a laudable goal, it is regressive because it transfers wealth from low- and fixed-income citizens to the benefit of well-off families. An additional inequity is that supporting institutional lunches disincentivizes families from packing wholesome meals from home. This is a moral

hazard that shifts dependency to a government unduly influenced by industrial actors.

Food should be purchased and prepared locally for all schoolchildren, and “Big Food” and “Big Sugar” should not be permitted in school cafeterias. Perhaps a bonus payment for schools that buy from small local producers could be established.

3. Nutrition guidelines, established jointly by USDA and HHS, must be updated, and they will be in late 2025. These guidelines set the standard for school meals. Strict adherence to the guidelines must be a requirement for school participation.

4. SNAP benefits should not cover sweet drinks. School cafeterias should not sell sweet drinks or chocolate milk.

5. Health classes should teach children about nutrition and even healthy weight loss diets. Diet and cooking clubs should be encouraged to teach students about healthy, tasty food choices. Adult diet and cooking classes should also be encouraged.

6. All federal nutrition programs must be Congressionally authorized, as should all CCC expenditures, especially when they fail to correspond with the CCC program’s original intent. Congress should close the loophole that allows broad use of CCC funds.

7. All federal beneficiary programs should result in a net benefit to the United States as well as to the individual beneficiaries. All programs should be required to assess their overall benefits. If the school lunch program increases the costs of healthcare later, neither the individuals nor the nation benefit from the program in the end.

8. The federal government must conduct a careful review and needs assessment to be sure its food and nutrition benefits are going to our economically neediest citizens. Beneficiaries should be incentivized to purchase the healthiest foods and receive sufficient funds to do so.

Appendix

Below is a list of all USDA food and nutrition benefit programs active in 2023

0 Comments